Executive Summary

The 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections in Ghana were marked by an unprecedented surge in anti-LGBTQI+ rhetoric, hate speech, and misinformation. Political leaders and campaigns from both major parties – the then ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC) – openly leveraged homophobic messaging as an electoral strategy. This created a charged environment in which LGBTQI+ issues were weaponised to sway voters, overshadowing substantive policy debate. By the end of this bitter campaign, former President John Dramani Mahama of the NDC won 7th December 2024 election with about 56% of the vote, and the NDC secured a two-thirds majority in Parliament, ending eight years of NPP rule. He was sworn into office on 7th January 2025, becoming the first Ghanaian leader to return to the presidency after a prior defeat. These outcomes underscore how deeply the anti-LGBTQI+ agenda had been interwoven with mainstream politics: both Mahama and his main opponent, former Vice President Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia, vied to appear tougher against LGBTQI+ rights throughout the campaign.

A central backdrop to the 2024 elections was the Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Bill, 2024, widely known as the “anti-LGBTQI+ bill”. Parliament had overwhelmingly passed this draconian bill on 28th February 2024, prescribing up to 3 years’ imprisonment for LGBTQI+ activity and harsher penalties for advocacy or expression of support. The bill enjoyed bipartisan support and reflected widespread anti-LGBTQI+ sentiment (surveys indicate 93% of Ghanaians disapprove of homosexuality). The 2025 Pew Research Center report (survey conducted Jan–May 2024) found that over 90% of Ghanaians say they would feel uncomfortable if they had a gay or lesbian child. Among religious subgroups, the data show that more than nine in ten Christians and Muslims in Ghana expressed this discomfort. This means that in both major faith communities, disapproval of LGBTQ+ identification (even hypothetically within one’s family) is deeply embedded. For politics, this is consequential: when over 90% of both Christians and Muslims share a strong negative emotional response, politicians can safely appeal to religious base fears with minimal electoral risk. The high levels of discomfort across both Christian and Muslim populations help explain why the Anti-LGBTQI+ Bill generated so much traction and why framing it as reflecting “public will” resonated strongly across major demographic groups.

However, the bill could not become law without presidential assent. Outgoing President Nana Akufo-Addo (NPP) unexpectedly declined to sign it before leaving office, even after Ghana’s Supreme Court dismissed legal challenges against the bill in December 2024. As a result, the bill “expired” when the 8th Parliament’s term ended on 6th January 2025. Akufo-Addo’s hesitance was widely attributed to international pressure – notably warnings that Ghana risked losing critical World Bank funding if the bill was enacted. Indeed, Ghana’s Finance Ministry and central bank had cautioned that signing the law could forfeit USD $3.8 billion in development support amid an economic crisis. This fueled accusations during the campaign that the NPP government was beholden to foreign interests and “lenient” on LGBTQI+ issues. Mahama capitalised on this narrative, alleging that Akufo-Addo’s reluctance to sign the bill was due to dependence on foreign aid. Mahama and the NDC presented themselves as more willing to defy international criticism and enshrine the anti-LGBTQI+ bill into law, a stance which they touted as “upholding Ghanaian values.” Ironically, Mahama’s victory means the bill’s fate now lies with a president who campaigned on supporting it – a sobering reality for human rights advocates.

This report by Rightify Ghana provides a detailed analysis of how anti-LGBTQI+ rhetoric, hate speech, and misinformation permeated Ghana’s 2024 election campaign. It examines candidate statements, incidents of hate speech and incitement, disinformation tactics (including homophobic campaign advertisements on TV, radio and social media), the role of party manifestos in weaponising LGBTQI+ issues, and the impact of this toxic climate on LGBTQI+ individuals. It also explores the international influences that shaped domestic anti-LGBTQI+ narratives during 2024. Finally, the report offers comprehensive recommendations to various stakeholders – from the Government and political parties to the media, civil society, international partners, and religious/traditional leaders – aimed at fostering a more inclusive democratic discourse and protecting the rights and safety of LGBTQI+ persons in Ghana.

Context as of September 2025:

President Mahama’s administration and the new NDC-dominated Parliament face crucial decisions on the lapsed anti-LGBTQI+ bill. The intense homophobic campaigning of 2024 has left a legacy of heightened social stigma and vulnerability for LGBTQI+ Ghanaians. Although the worst-case legislative scenario (formal enactment of the bill) was averted by the previous president’s inaction, the climate of intolerance remains acute. Ensuring that Ghana upholds its constitutional principles of freedom and justice for all – rather than entrenching state-sanctioned discrimination – is more urgent than ever. The recommendations in this report urge a range of actors to counter hate speech and misinformation, protect marginalized communities, and promote a more inclusive democracy going forward.

Candidate Statements and Campaign Positions on LGBTQI+ Issues

Mahamudu Bawumia (NPP) – Dr. Bawumia, the ruling NPP’s 2024 presidential candidate (and then–Vice President), made anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment a centerpiece of his campaign. Throughout 2024, Bawumia emphatically promised that under his presidency LGBTQI+ activities would have no place in Ghana. He often framed this as a matter of non-negotiable principle: “No ifs or buts. No shades of grey,” he declared, insisting that neither Islam (his faith) nor Ghanaian culture tolerates homosexuality. In one instance, during an Eid celebration in Kumasi, he told a Muslim audience that Ghana “will never accept LGBT+, no matter the consequence”. Bawumia pledged to “stand firm against LGBTQ activities… no matter the consequences”, signaling he would even risk international backlash to uphold what he called “Ghana’s family values”. He repeated these vows at rallies and meetings across the country – from assuring clergy in Tamale that he would ban LGBTQI+ activities by law, to telling supporters in Cape Coast that “no man will be marrying a man in Ghana” under his watch. Bawumia explicitly aligned himself with the controversial anti-LGBTQI+ bill, indicating he would sign it into law without hesitation. His manifesto and speeches cast this stance as defending Ghana’s cultural sovereignty and religious morality. Indeed, the NPP’s 2024 manifesto included strong anti-LGBTQ+ proposals as a central element, reinforcing Bawumia’s focus on “proper human sexual rights” and Ghanaian family values. This was no surprise given that the NPP’s manifesto committee chairman was Hon. Osei Kyei-Mensah-Bonsu, a key supporter of the anti-LGBTQI+ bill in Parliament during the months leading to its passage. Bawumia’s alignment with hardline anti-LGBTQI+ activists was also evident – for example, he maintained close ties with Moses Foh-Amoaning (leader of the National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values), even publicly celebrating their friendship during his speech as special guest at his 60th birthday in March 2024. In sum, Bawumia left no ambiguity about his position: he portrayed himself as an uncompromising defender of Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ status quo, hoping to galvanise conservative voters.

Timeline of Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia’s Statements

- Bawumia rejects LGBTQ in emphatic Eid Message: Says “no ifs or buts. No shades of grey.”

Vice President and flagbearer of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia, strongly rejected the practice of LGBTQ in Ghana during his Eid message to Muslims in Kumasi on April 11, 2024. He emphasized that neither his religion, Islam, nor Ghanaian culture supports homosexuality, stating that both Christianity and Islam clearly oppose such practices. - I won’t allow LGBTQ activities in Ghana, no matter the consequences – Bawumia

In a meeting with the clergy in Tamale on May 16, 2024, Dr. Bawumia firmly stated that he would not permit LGBTQ activities in Ghana if elected president. He emphasized that this stance was supported by both the Bible, the Quran, and the people of Ghana. - LGBTQ+ will not be allowed to happen in Ghana under my presidency – Bawumia reassures

During his Northern Region tour on May 16, 2024, Dr. Bawumia reiterated his position that LGBTQ+ activities would not be allowed under his presidency. He cited both his religious beliefs and Ghana’s cultural values as reasons for his stance. - Anti-LGBTQ: Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia Doubled Down on His Homophobic Stance During Northern Region Tour

Dr. Bawumia again emphasized his opposition to LGBTQ activities during his tour in the Northern Region on May 16, 2024, asserting that both Christianity and Islam, as well as Ghanaian society, are against it. - I will stand firm against LGBTQ activities in Ghana no matter the consequences – Vice President and Flagbearer of the NPP, Dr. Bawumia

Dr. Bawumia affirmed his commitment to standing firm against LGBTQ activities in Ghana on May 17, 2024, stating that he would not allow such activities regardless of external pressures or consequences. - ‘I’ll not allow LGBTQ activities in Ghana’ – Vice President and Flagbearer of the NPP, Dr. Bawumia

Dr. Bawumia reiterated his stance on LGBTQ during his campaign tour on May 16, 2024, stating that he would not permit LGBTQ activities under his leadership. - No man will be marrying a man in Ghana – Vice President and Flagbearer of the NPP, Dr. Bawumia reaffirms anti-LGBTQ stance

During his campaign on May 16, 2024, Dr. Bawumia reaffirmed that same-sex marriage would not be allowed in Ghana, citing both religious and cultural objections. - Ghana will never accept LGBT+, no matter the consequence – Bawumia

In a statement made in Dambai, the capital of Oti Region on June 2, 2024, Dr. Bawumia emphasized that Ghana would not accept LGBTQ practices, stressing cultural and religious opposition. - I’ll firmly protect Ghana’s family, cultural values against LGBTQ – Bawumia

Dr. Bawumia told a gathering in Cape Coast on June 3, 2024 that his government would ensure LGBTQ+ activities are not legalized in Ghana. He compared the rejection of same-sex marriage to the non-acceptance of polygamy in other jurisdictions.

John Dramani Mahama (NDC) – As the NDC’s presidential candidate and a former head of state, John Mahama likewise espoused openly anti-LGBTQI+ views during the campaign, despite his party’s traditionally more liberal image in other policy areas. Mahama frequently anchored his opposition to LGBTQI+ rights in his personal faith. Citing his membership in the Assemblies of God Church, he asserted that “my faith is against LGBTQ+”, and that same-sex marriage and related practices are incompatible with Christian (and Muslim) beliefs in Ghana. On the campaign trail, Mahama vowed to strengthen laws against LGBTQ+ activities if elected, pledging to prevent any pro-LGBTQI+ developments in schools or communities. He positioned himself as someone who would do what his opponent’s NPP government had not – namely, ensure the anti-LGBTQ+ bill became law. Mahama lambasted President Akufo-Addo for failing to sign the bill, insinuating that the delay was because the NPP cared more about pleasing Western donors than reflecting Ghanaian values. “Akufo-Addo is refusing to sign the anti-gay bill due to foreign aid,” Mahama alleged in March 2024, tapping into public resentment that Ghana’s sovereignty was being traded for money. He and other NDC figures repeatedly accused the NPP of being secretly soft on LGBTQI+ issues – a striking role reversal given that the NDC historically had champions of the anti-LGBTQ+ bill within its ranks as well. Mahama also adopted the popular rhetoric that LGBTQI+ identities are a “Western import” contrary to Ghanaian culture. He argued that Western nations were hypocritical for pressuring African countries to respect LGBTQI+ rights “despite their [own] religious and cultural opposition” at home, referencing the influence of evangelical conservatives in the US and elsewhere. Thus, Mahama framed his anti-LGBTQI+ stance as both culturally authentic and resistant to neocolonial influence. Notably, in the final days of the campaign, Mahama went on international media to bolster his credentials; in a BBC interview just before the vote, he again stressed his opposition to homosexuality in line with Ghana’s “cultural and religious values”. By taking such a hard line, Mahama neutralised NPP attempts to paint him as “pro-gay” and reassured voters that an NDC government would be just as – if not more – hostile to LGBTQI+ rights. Indeed, international observers noted with concern that Mahama explicitly supported the anti-LGBTQ bill passed by Parliament, despite its global condemnation. In effect, both major candidates in 2024 ran on anti-LGBTQI+ platforms, leaving LGBTQI+ Ghanaians without any major party champion of their rights.

Timeline of John Mahama’s Statements

- Opposition to LGBTQ+ Rights:

John Mahama, former President of Ghana and presidential candidate for the NDC in the 2024 elections, expressed opposition to LGBTQ+ rights, particularly same-sex marriage on January 31, 2024. He consistently stated that his faith, as a member of the Assemblies of God Church, does not support LGBTQ+ activities and aligns with traditional Christian views against same-sex relationships. - Faith-Based Position on LGBTQ+:

Mahama emphasized that his opposition to LGBTQ+ rights is rooted in his religious beliefs on January 31, 2024. He voiced that his faith does not permit same-sex relationships, human-animal relationships, or gender changes at will. This position was reiterated during a campaign event where he vowed to strengthen laws against LGBTQ+ activities if elected. - Criticism of President Akufo-Addo’s Stance on the Anti-LGBTQ+ Bill:

Mahama criticized President Akufo-Addo for not signing the anti-LGBTQ+ bill into law on March 12, 2024, suggesting that the delay is influenced by concerns about foreign aid. He also called on the President and Parliament to remove clauses from the bill that may impose costs on the state or infringe on the Constitution. - Advocacy for Stronger Anti-LGBTQ+ Legislation:

Mahama pledged to strengthen laws against LGBTQ+ activities if elected on January 31, 2024. He promised to prevent the promotion of LGBTQ+ activities in schools and communities, ensuring that LGBTQ+ rights are not advanced under his leadership. - Cultural and Religious Arguments Against LGBTQ+:

Mahama views LGBTQ+ as a “Western import” that contradicts Ghanaian cultural values and religious teachings on January 31, 2024. He pointed out that many Western countries, including the U.S., face internal opposition to LGBTQ+ rights, especially from evangelical Christians. He contended that Western countries exert pressure on African nations, like Ghana, to support LGBTQ+ rights, despite their religious and cultural opposition. - Support for Anti-LGBTQ+ Bill and Cultural Protectionism:

Mahama has expressed concern over the delays to the anti-LGBTQ+ bill on November 30, 2024, warning that the bill may expire if not passed soon. He has urged Ghanaians to protect children from what he calls “indoctrination” into LGBTQ+ practices, aligning his position with the views of many religious leaders in Ghana who oppose LGBTQ+ rights.

Other Presidential Candidates and Political Figures: The pervasive anti-LGBTQI+ climate extended beyond the two front-runners. Alan Kwadwo Kyerematen, a prominent third-party candidate (Movement for Change) and former NPP minister, similarly took a vehement anti-LGBTQI+ position. At an Institute of Economic Affairs forum in October 2024, Kyerematen declared: “I oppose LGBTQ+ rights to the fullest extent possible. … LGBTQ+ goes against my faith and our social values.” He even implored President Akufo-Addo and the Chief Justice to ensure the family values bill became law, reflecting a consensus among candidates to outdo each other in opposing LGBTQI+ acceptance. Other political actors who had previously shown nuance were pressured to conform. For instance, Mr. Francis-Xavier Sosu, an NDC MP known as a human rights lawyer, faced criticism within his party in early 2024 over a mild comment he made about the anti-LGBTQ bill (which some colleagues took as insufficiently enthusiastic). In response, Sosu visibly hardened his stance as elections neared (as discussed further below). Additionally, vocal proponents of the anti-LGBTQI+ bill, such as NDC MP Samuel Nartey George (Sam George) and NPP MP Rev. John Ntim Fordjour, were elevated in their parties and on campaign platforms. Sam George, in particular, became a high-profile surrogate for Mahama on this issue, boasting of NDC’s commitment to fight “trumu trumu” (a derogatory term for homosexuality) at rallies. The strong anti-LGBTQI+ consensus across political lines meant that LGBTQI+ people were used as a convenient scapegoat and social wedge throughout the campaign. No major party offered a dissenting view; instead, the debate was over who would be tougher on LGBTQI+ communities. This set the stage for an election rife with inflammatory speech and propaganda targeting sexual minorities.

Alan Kyerematen’s statements regarding his opposition to LGBTQ+ rights:

- Alan Kyerematen Urges President Akufo-Addo to Sign Anti-LGBTQ Bill, Reaffirms Strong Opposition

Alan Kyerematen, presidential candidate for the Movement for Change, voiced his opposition to LGBTQ+ rights and urged President Akufo-Addo to sign the anti-LGBTQ+ bill into law during the IEA’s 2024 Evening Encounter on October 1, 2024. He reaffirmed his stance, saying, “I oppose LGBTQ+ rights to the fullest extent possible. This goes against my faith and our social values.” He also called on Chief Justice Torkornoo to prioritize public policy interest in the ongoing legal deliberations. - LGBTQ+ is against my faith and our social values – Alan Kyerematen

In his appearance at the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) Evening Engagement in Accra on October 1, 2024, Alan Kyerematen reiterated his strong opposition to LGBTQ+ rights, emphasizing that such rights go against his faith and Ghana’s social values. He also urged Chief Justice Torkornoo to consider public policy interests in the ongoing legal proceedings regarding the LGBTQ+ bill, and called for President Akufo-Addo to sign the bill into law.

Kyiri Abosom’s statements:

- Kyiri Abosom Vows to Promote Polygamy, Doubts Passage of Anti-LGBTQ Bill

Christian Kwabena Andrews, popularly known as Osofo Kyiri Abosom, presidential candidate for the Ghana Union Movement (GUM), stated during an interview with Kasapa FM on October 2, 2024, that he would advocate for all men to marry at least five wives under his leadership. In response to a question on LGBTQI+, he expressed doubt that President Akufo-Addo would sign the anti-LGBTQ bill into law. He emphasized promoting polygamy instead, urging men to marry multiple wives to “fill the earth” as per God’s will. Despite being a pastor, he mentioned that he does not believe in the Bible or its content. - ‘I will tag President Akufo-Addo as gay if he refuses to sign anti-gay bill’ – Kyiri Abosom

In this statement on March 5, 2024, Kyiri Abosom vowed to label President Akufo-Addo as “gay” if he refuses to sign the anti-LGBTQ bill into law. - I will advocate for all men to marry at least five wives – Osofo Kyiri Abosom

Kyiri Abosom further discussed his intention to advocate for polygamy, specifically encouraging all men to marry at least five wives as part of his vision for Ghana on October 5, 2024.

Kofi Akpaloo’s statements:

- Kofi Akpaloo Claims LGBTQ+ Doesn’t Exist in Ghana, Alleges Paid Anti-Gay Campaigns Are Promoting It

Kofi Akpaloo, the presidential candidate for the LPG, claimed during an interview with Kasapa FM in Accra on October 5, 2024 that LGBTQ+ does not exist in Ghana. He alleged that some individuals are being funded to raise awareness of LGBTQ+ issues and that campaigns against it are, in effect, promoting it through “reverse psychology” by increasing awareness. - No president in his right sense will sign anti-gay bill now – Kofi Akpaloo

Kofi Akpaloo expressed that no rational president would sign the anti-gay bill at this time on March 22, 2024. - Anti-LGBTQ+ Bill: Throw it in the dustbin – Kofi Akpaloo tells Akufo-Addo

In another interview on March 19, 2024, Kofi Akpaloo urged President Akufo-Addo to discard the anti-LGBTQ+ bill, advising against its passage.

Hassan Ayariga’s statements:

- Waste no time, sign Anti-LGBT+ Bill into law – Ayariga to Akufo-Addo

Hassan Ayariga, founder and flag bearer of the All People’s Congress (APC), urged President Akufo-Addo to act swiftly and sign the Anti-LGBTQ+ bill into law on March 10, 2024, emphasizing the importance of affirming Ghana’s cultural values. - Ayariga explains why Akufo-Addo is not signing anti-gay bill

Ayariga criticized African leaders, including President Akufo-Addo, for lacking decisive leadership and being influenced by external forces on November 8, 2024. He expressed skepticism that the President would sign the Anti-LGBTQ+ bill, suggesting that there may be external interests preventing its passage. - ‘Walk your talk and sign the Anti-gay bill into law’ – Hassan Ayariga tells Akufo-Addo

Ayariga again urged President Akufo-Addo to follow through on his previous statements and sign the Anti-LGBTQ+ bill on March 10, 2024, stressing the importance of adhering to Ghana’s traditional values.

Nana Kwame Bediako’s (Cheddar) statements:

- ‘I don’t know the main objectives of the anti-LGBTQ Bill’ – Nana Kwame Bediako refuses to declare stance on the Bill

Ghanaian businessman and leader of #TheNewForce movement, Nana Kwame Bediako, declined to declare his stance on the Anti-LGBTQ Bill when asked during an interview on Asempa FM’s Ekosiisen on January 16, 2024. He emphasized that his Christian faith does not encourage judgment of others and expressed uncertainty about the bill’s objectives. - Remember, subtle or explicit—homophobia is still homophobia

Nana Kwame Bediako made remarks that were considered subtly homophobic in September 2024. Whilst engaging some traditional leaders, he falsely claimed that U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris made calls for the legalisation of same-sex marriage in Ghana. He added that it was against Ghanaian cultural values. Rightify Ghana highlights that, like other political figures, Bediako’s stance on LGBTQ+ issues is critical, particularly as his statements and behaviour during the 2024 election campaign resemble the homophobic rhetoric of other politicians such as John Mahama (NDC) and Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia (NPP).

The Assin North Experiment: Homophobia as a Political Strategy

The use of homophobia as a deliberate political strategy in Ghanaian elections did not emerge suddenly in 2024, it was sharpened during the Assin North by-election of June 27, 2023. In that contest, the opposition NDC framed its campaign around anti-LGBTQI+ fears, telling voters that the ruling NPP wanted to capture the seat in order to “legalise LGBTQ” in Ghana. Campaigners went house to house claiming that President Akufo-Addo had removed James Gyakye Quayson from Parliament to create space for pro-LGBTQI laws, and that a win for the NPP candidate, Charles Opoku, would lead to the Speaker of Parliament being replaced to push same-sex marriage through. In reality, the bill before Parliament was an anti-LGBTQI+ bill, not one promoting LGBTQI+ rights.

This rhetoric was repeated publicly. On June 3, 2023, NPP’s Miracles Aboagye accused the NDC on TV3’s Key Points of lying to voters by saying Akufo-Addo wanted “numbers to pass an LGBTQI law.” The next day, June 4, 2023, NDC legal team member Godwin Edudzi Tamakloe told TV3’s NewDay programme that Akufo-Addo and Bawumia needed the Assin North seat to block the anti-LGBTQI+ bill and pass “obnoxious laws” to destroy Ghana’s moral fabric. These claims, while demonstrably false, resonated strongly in a constituency where suspicion of LGBTQI+ issues runs high. Videos of NDC campaigners spreading similar narratives circulated widely on social media, reinforcing the message that voting NDC meant “defending Ghana’s family values.”

The NPP countered by denouncing these allegations as misleading, with spokespersons such as Gyewu-Appiah insisting that claims about same-sex marriage were unfounded. Yet the ruling party also used the moment to restate its hardline opposition to LGBTQI+ rights, careful not to appear sympathetic. Both parties thus competed on homophobic grounds, vying for legitimacy by signaling hostility to LGBTQI+ people.

When the NDC’s James Gyakye Quayson won the seat, the party quickly linked the victory to its anti-LGBTQI+ stance. At a thank-you rally in Assin Bereku in July 2023, NDC National Communications Officer Sammy Gyamfi declared that the defeat had “forced” NPP MPs into backing the anti-LGBTQI+ bill in Parliament. Parliamentary debates days later turned into a contest of which side could sound more anti-LGBTQI+, with lawmakers outdoing each other in homophobic rhetoric. The message was clear: Assin North had shown that appealing to anti-LGBTQI+ sentiment was a winning electoral tactic.

This “Assin North experiment” set the stage for the 2024 general elections, where both major parties scaled up the strategy on a national level.

By 2024, homophobia was no longer just a social prejudice, it had become an entrenched political weapon. What began in Assin North as a constituency-level experiment in misinformation and fearmongering had, within a year, been elevated into a national electoral strategy. Both the NDC and NPP entered the presidential and parliamentary races convinced that stoking anti-LGBTQI+ sentiment was an effective means of mobilising voters. The tragic consequence was a political landscape where truth was distorted, hate speech was normalised, and LGBTQI+ Ghanaians were left more vulnerable than ever.

Hate Speech and Incitement During the Campaign

The 2024 campaign saw disturbing instances of outright hate speech and incitement against LGBTQI+ persons, often led or encouraged by politicians seeking to whip up popular fervor. Perhaps the most glaring example occurred at the NDC’s final rally in Madina (Accra) on December 5, 2024. There, MP Francis-Xavier Sosu – a lawyer who, ironically, had a past reputation for defending human rights – led the crowd of thousands in a call-and-response chant that openly vilified gay people. “When I say trumu trumu [a slur for ‘gay’], you say away!” Sosu shouted, and the crowd roared back “Away!” repeatedly. This homophobic chorus was performed enthusiastically four times, as captured on video, effectively turning an anti-LGBTQ slogan into a rally cheer. The fact that Sosu resorted to such demagoguery highlights how politically expedient homophobia had become – even figures known for legal advocacy felt compelled to incite the public against a vulnerable minority to prove their loyalty to the party line. The trumu trumu – away chant not only dehumanised LGBTQI+ people but also carried an implicit encouragement of societal rejection (“send them away”) that many fear could translate into harassment or violence. Human rights observers described the spectacle as “bigotry on display” and noted the “fervent anti-LGBT climate” it reflected.

Sosu was not alone. NDC’s firebrand MP Sam George, a leading proponent of the anti-LGBTQI+ bill, also used incendiary language at the same rally and others. He framed the election as a referendum on homosexuality: “A vote for Mahama is a vote to protect our culture and family values. A vote for Bawumia … is a vote for homosexuality… No to trumu trumu!”. The crowd cheered as Sam George explicitly cast the ruling party as agents of an alleged “gay agenda”, despite the NPP candidate Bawumia having loudly denounced homosexuality throughout his campaign. Such rhetoric – equating one’s political opponents with promoting homosexuality, which is widely despised – amounted to a smear designed to stoke fear and hatred. It told Ghanaians that supporting the NPP would somehow invite moral ruin, effectively demonizing not only LGBTQI+ people but also anyone who didn’t support the anti-LGBTQI+ crusade.

On the NPP side, there were likewise instances of hateful or threatening language, though the NPP generally relied more on moralistic condemnation than rally chants. One notable incident involved Hon. Matthew “Napo” Opoku Prempeh, Bawumia’s running mate. At a rally in Bantama, Kumasi in October 2024, Napo alleged that the NDC (when last in government) had taught students “how a man kisses a man and how a woman sleeps with a woman” – a gross distortion meant to incite outrage (this false claim is examined in the next section). The crowd’s hostile reaction to this alleged LGBTQ+ “curriculum” was precisely the intent. While not a direct slur, Napo’s narrative painted LGBTQI+ behavior as predatory (targeting schoolchildren) and implicitly invited the public to view the NDC – and by extension LGBTQI+ people – as dangerous corrupters of society.

Religious and traditional figures also sometimes crossed into hate speech during the campaign period, amplifying the rhetoric. Although the focus of this report is on the campaign proper, it is worth noting that many political rallies featured pastors and local chiefs who prayed against the “abomination” of homosexuality or exhorted listeners to “defend our land from Sodom and Gomorrah” imagery. Such language, while couched in scripture, contributes to an atmosphere of incitement by suggesting divine sanction for intolerance. For example, less than a week before the vote, Bawumia visited a prominent church where he vowed to ensure the anti-LGBTQ law “comes to be” if he wins; the church audience responded with approval, reinforcing a union of political and religious anti-LGBTQ fervor.

The cumulative effect of these instances of hate speech was to normalise open public hostility toward LGBTQI+ people in a way not seen before in Ghana’s Fourth Republic. What might once have been confined to private pulpits or fringe discourse was blasted through megaphones at campaign rallies and on national media. Crowd dynamics (such as the Madina chant) created performative hate, where thousands of ordinary citizens were chanting along to derogatory slurs. This not only degrades public debate but poses a real risk of vigilante action. By campaign’s end, many LGBTQI+ Ghanaians feared that such charged rhetoric could be a prelude to physical attacks or communal “witch hunts.” Indeed, observers called the Madina rally chants “especially terrifying for the LGBTI community in Ghana”, noting that both leading parties had made anti-LGBT sentiments a litmus test for leadership. The hate-filled language of 2024 has set a dangerous precedent, effectively giving social approval to homophobia as a legitimate campaign tool – something that must be urgently addressed to prevent backsliding on basic rights and civility.

Disinformation and Anti-LGBTQI+ Propaganda

Misinformation and False Narratives:

Alongside overt hate speech, the 2024 elections were awash with disinformation targeting LGBTQI+ issues. False claims and conspiracy theories were deployed by partisans on all sides, illustrating how sexual minorities became pawns in Ghana’s information wars. A Fact-Check Ghana investigation found that throughout 2024, politicians were both perpetrators and victims of LGBTQ+-related disinformation, as rumors were weaponised to tarnish opponents’ reputations. For instance, John Mahama was persistently smeared on social media by a network of pro-NPP accounts alleging that he “supports homosexuality” and even has secret gay benefactors. In late 2023, viral posts on X (Twitter) circulated a photo of Mahama with prominent gay rights advocate Andrew Solomon, with captions suggesting Solomon was Mahama’s “gay partner and financier”. Another rumor linked Mahama to a British LGBTQ+ public figure, attempting guilt by association. These insinuations – entirely baseless – played on the idea that Mahama was beholden to an international “gay lobby.” The narrative was bolstered by homophobic tropes; one tweet claimed that people hated Bawumia “because as a Muslim he won’t entertain their gay agenda” and posted a photo of Mahama “in bed with gay activists” to imply he was literally in league with them. Mahama and his former Minister Nana Oye Lithur were accused in coordinated posts of plotting to legalise gay rights if they regained power. These claims were recycled from earlier propaganda – they had surfaced in years past – but 2024 saw them amplified anew across X, Facebook, and WhatsApp. In reality, Mahama has consistently opposed LGBTQ+ rights (as documented above), and Andrew Solomon himself publicly debunked the rumors in a 2013 New York Times piece titled “In Bed with John Mahama”. Solomon flatly refuted being Mahama’s partner or donor, underscoring how absurd the disinformation was. Nonetheless, the persistence of these falsehoods during the campaign shows how deeply entrenched the notion of an “LGBTQ+ conspiracy” had become in political mudslinging.

The ruling NPP’s camp was also targeted by defamatory LGBTQ-related rumors. After Dr. Bawumia named Dr. Matthew “Napo” Opoku Prempeh as his running mate in July 2024, a new disinformation campaign erupted – this time accusing Napo himself of being gay. The fact that Napo was unmarried until age 55 was twisted by opponents into a story that he “could not be with a woman” and had hastily married only to cover up his homosexuality. This narrative first gained traction on pro-NDC radio shows in Accra and was then amplified on TikTok and Facebook. Even some NPP figures-turned-dissidents fueled the rumor: a former NPP official, Hopeson Adorye, publicly claimed “Napo is allegedly GAY and only got married due to pressure… I have photos and videos as evidence”. No evidence was ever produced, and the allegation was unfounded. But it spread widely online via a “plethora of handles” that consistently pushed the narrative that Napo had a hidden LGBTQ agenda. In short, each side accused the other of harboring closeted gay men who would stealthily advance LGBTQI+ interests – a bizarre paradox given both Bawumia and Mahama were loudly anti-LGBT. The goal of these mirror-image smears was less about convincing the public of factual truth and more about associating opponents with something already demonized in the public mind. As Fact-Check Ghana observed, any politician whose anti-gay bona fides were not iron-clad risked being “targeted by opponents as a supporter of homosexuals.” The result was a race to the bottom in which truth mattered little.

Fabricated “LGBTQ+ Agenda” in Education:

Disinformation was not limited to personal attacks; it also targeted policies and institutions. A salient example is the false claim of an LGBTQ+-influenced school curriculum. During the campaign, NPP vice-presidential nominee Napo Opoku Prempeh alleged at a rally that the NDC, when last in government, had introduced a Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) curriculum teaching children how to engage in same-sex intimacy. “They [NDC] rallied pastors and imams… telling teachers to teach schoolchildren how a man kisses a man and how a woman sleeps with another woman. All these things have happened in Ghana,” Napo declared to an aghast crowd. He further insinuated that Mahama’s supposed “gay partner” Andrew Solomon funded a book project as part of this agenda. These incendiary claims were blatantly false. In reality, Ghana’s attempt to introduce a CSE framework was a national policy effort in 2019 (under the NPP government with Napo as Education Minister) aimed at better sexual health education – and it never included anything as salacious as teaching same-sex techniques. Fact-checkers revealed Napo’s hypocrisy: back in 2019, he publicly supported integrating CSE into the curriculum, stating it was “imperative… that sexuality education should be part of the curricula… from kindergarten to senior high school”. Thus, the very individual who helped roll out CSE later pretended it was an NDC “gay agenda” to score political points. His allegation about pastors and imams being “rallied” to promote homosexuality in schools was a fabrication designed to inflame religious sensibilities. NDC figures like Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa and Prof. Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang (a former Education Minister) immediately refuted Napo’s story, calling it a “desperate fabrication” and challenging him to provide any evidence. No evidence was produced. Nonetheless, the myth of a secret pro-LGBTQ+ curriculum spread quickly among voters through word-of-mouth and WhatsApp forwards. It exemplified how misinformation exploited existing fears – in this case, the longstanding moral panic that “gay activists” are targeting school children. By evoking this specter, politicians like Napo sought to cast themselves as saviors protecting the youth from an invented threat. This narrative not only misled the public but also maligned Ghana’s genuine public health educators and jeopardized constructive discourse on sex education.

Homophobic Campaign Advertisements:

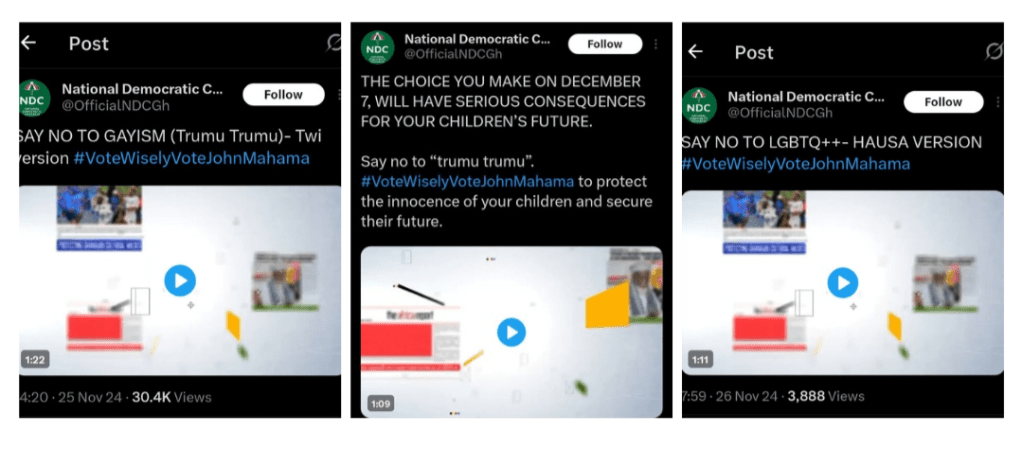

In 2024, both major parties took the unprecedented step of producing explicitly anti-LGBTQI+ attack ads for television, radio, and social media – a new low for Ghana’s political advertising. The NDC and NPP each circulated campaign videos that traded in homophobia, fear-mongering, and misinformation:

- NDC’s Anti-LGBTQI+ Ads: The National Democratic Congress created a series of ads (in multiple languages: Twi, Hausa, English) which portrayed the ruling NPP as secretly pro-LGBTQ+. These ads spread egregious misinformation about LGBTQ+ “practices” and featured footage of effeminate-looking men at NPP rallies, insinuating that the NPP attracted or harbored gay men. In one such ad, the NDC went so far as to label specific individuals seen dancing at NPP events as known “LGBTQ members,” a tactic that risked outing those individuals to potential harm. The voice-overs and text in the ads presented the NDC and Mahama as the only ones who would ensure the anti-LGBTQ+ bill becomes law, effectively claiming “Vote for Mahama to protect Ghanaian values; vote for NPP and you vote for homosexuality.” NDC messaging blatantly framed their party as “the most homophobic” alternative – an astonishing slogan, but one they calculated would resonate with voters given societal attitudes. These ads also included false or distorted “facts” about LGBTQI+ life – for example, suggesting that LGBTQ+ people seek to impose their lifestyle on others or that Ghana’s moral fabric had already been undermined by NPP’s tolerance. By drumming up fear, the NDC ads aimed to turn conservative and undecided voters against the incumbents. However, they did so at the expense of truth and the safety of actual LGBTQI+ Ghanaians who were implicitly painted as enemies of the state.

- NPP’s Anti-LGBTQI+ Ad: The NPP quickly countered with its own homophobic campaign ad, targeting Mahama. The centerpiece of the NPP ad was a doctored narrative: they dug up a decade-old video clip of then-President Mahama speaking about health services for gay men. In that interview, Mahama had acknowledged the need to reduce stigma so that men who have sex with men (MSM) could access healthcare without fear. This nuanced public health comment was twisted wildly out of context – the NPP ad presented Mahama’s quote (“we need to remove stigma… allow LGBTQ+ people to come out…”) as evidence that he was a proponent of LGBTQ+ rights and even “encouraging” people to be gay. The ad spliced Mahama’s quote to sound as if he was prioritizing LGBTQI+ issues, and paired it with footage of Mahama at a rally where an effeminate man was dancing near him. The implication was that Mahama is “sympathetic” to LGBTQI+ folks and would promote their agenda if elected. This was patently misleading – Mahama’s actual record was to oppose LGBTQI+ legal recognition, but the NPP sought to cast doubt using visual innuendo. The ad then featured Dr. Bawumia himself, looking stern, vowing that “LGBT+ will not be allowed to happen in Ghana under my presidency” – reinforcing his pledge to resist LGBTQI+ rights even under international pressure. Bawumia’s closing line in the ad emphasized that he’d stand firm “at all costs, especially against sanctions from international partners”, turning his stance into a show of anti-Western defiance. In essence, the NPP’s message was “Mahama is secretly pro-gay; Bawumia will defend Ghana.” To the extent Mahama had ever shown a modicum of tolerance (like acknowledging MSM need healthcare), it was now weaponized against him. This ad relied on fear by association and the manipulation of Mahama’s past words – a clear example of disinformation through video propaganda.

Both sets of ads were broadcast on mainstream media and disseminated on Facebook, WhatsApp, TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube, reaching millions of Ghanaians. They represent a dangerous new front in political propaganda: deploying homophobia in slick, emotive audio-visual form. The significance of these ads cannot be overstated. As noted by civil society monitors, 2024 was the first time Ghana’s major parties had openly leveraged homophobic imagery and tropes in nationwide campaign advertising. This signaled an escalation, taking anti-LGBTQI+ messaging from speeches into polished campaign materials, thereby further legitimising it. The ads fueled public misconceptions – for example, falsely suggesting that there was a real possibility of same-sex marriage or an “LGBTQ takeover” in Ghana unless voters chose the “right” candidate. They also contributed to an atmosphere of hysteria and moral panic ahead of the polls. Notably, these tactics coincided with a period of economic hardship in Ghana; rather than focus exclusively on economic plans, both parties leaned into identity politics. Scapegoating a vulnerable minority became a convenient distraction and rallying cry.

Disinformation and propaganda around LGBTQI+ issues in the 2024 campaign were pervasive and cut both ways. False narratives – from personal smears (Mahama or Napo are “gay”) to fearmongering about children’s education – were deliberately spread to exploit prejudice. Homophobic campaign ads cemented those narratives in the public consciousness through repetition and visceral imagery. The objective was to present one’s political opponents as morally unfit and to claim the mantle of “true cultural defender” for oneself. The casualty in all this was truth – and the dignity and safety of LGBTQI+ Ghanaians, who were caricatured as a menace. This election underscored how easily disinformation can thrive in an environment where a topic (like LGBTQI+ rights) is already poorly understood and stigmatized. It also demonstrated the need for fact-checking bodies and media regulators to more proactively counter election-related falsehoods. Unfortunately, in 2024 the misinformation largely went unchecked in real time, leaving lasting myths that could continue to fuel hate beyond the election season.

Political Party Manifestos and Weaponisation of LGBTQI+ Issues

Despite the ferocity of anti-LGBTQI+ rhetoric on the campaign trail, the formal manifestos of the major parties were relatively muted on this issue – likely by design, to avoid international scrutiny. Nevertheless, LGBTQI+ issues were implicitly weaponised as a core political tool in 2024, even if not always explicitly written in manifestos.

The ruling NPP’s 2024 manifesto did incorporate references to “family values” and opposition to LGBTQI+ rights as part of its social policy agenda. According to insider accounts, the NPP included “strong anti-LGBTQ+ proposals” in the manifesto, aligning with Dr. Bawumia’s public pledges. This is consistent with Bawumia’s campaign, which centered on promoting “Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values” – echoing the title of the pending bill. The manifesto’s emphasis on conservative cultural values signaled to voters that an NPP government would not allow any pro-LGBTQI+ reforms. The influence of key anti-LGBT figures on the manifesto is notable: the drafting committee was chaired by Osei Kyei-Mensah-Bonsu, who as Majority Leader had championed and even toughened the anti-LGBTQI+ bill in Parliament. His involvement ensured that opposition to LGBTQI+ rights was enshrined as a pillar of the NPP’s platform, giving Bawumia a written commitment to point to when countering any skepticism about his stance.

In contrast, the NDC’s 2024 manifesto did not explicitly highlight the anti-LGBTQI+ bill or related policies in writing. The NDC likely chose to avoid a prominent mention, perhaps to maintain some plausible deniability on the international stage or because the bill’s eventual passage was assumed and did not need reiteration. However, this absence in print was more than compensated by the NDC’s outspoken use of the issue in the campaign. Rather than a line in a manifesto, the NDC weaponised LGBTQI+ matters through speeches, rallies, and advertising. The party presented itself as the true vehicle to pass the “Family Values Bill” – essentially making that promise an informal manifesto plank, even if not written. For example, NDC Chairman Johnson Asiedu Nketia and others at rallies repeatedly assured supporters that Mahama would sign the bill at the first opportunity, contrasting him with Akufo-Addo who “failed” to do so. In effect, the NDC’s campaign messaging served as a parallel manifesto on LGBTQI+ issues, one that was even more hardline than the NPP’s formal document. This approach allowed the NDC to capitalise on public sentiment without having to detail policy specifics. It was a calculated strategy: use homophobia as an emotive rallying point, while focusing the official manifesto on bread-and-butter issues to avoid external backlash.

The result was that LGBTQ+ issues became a potent “wedge” in the election, arguably outstripping debates on education, health, or other social policies in visibility. Both parties used the specter of LGBTQI+ rights as a cudgel against each other. The NDC claimed the NPP was too soft or incompetent to get the anti-LGBT law enacted; the NPP claimed the NDC was hypocritical (pointing to Mahama’s past tolerance in context of public health) and that NDC’s attacks were a smokescreen for their own failures. Each side essentially dared the other to prove how anti-LGBT they could be. This dynamic hijacked the campaign discourse. As one analysis put it, “anti-homosexuality or anti-gay rights [became] the main campaign tool… the moral and emotional vehicle” for both NDC and NPP to gain support. In a nation facing a severe economic crisis, it is telling that moral panic was deployed alongside economic critique. Indeed, Mahama skillfully blended the two: he hammered the NPP for the economic collapse, but also insinuated that under NPP the nation’s moral fabric was endangered (by their inability to outlaw LGBTQ+). The NPP, for its part, touted any economic stabilization as meaningless if “our values” were lost, thus tying prosperity to conservative social policy.

It is important to note that Ghana’s political context made this weaponisation feasible. Public opinion against LGBTQI+ inclusion was so high that there was no apparent electoral downside to homophobic positioning. Unlike some democracies where a harsh anti-minority stance might alienate a portion of voters, in Ghana 2024 it was seen as only a vote-winner. Neither party feared a backlash for promoting illiberal policies toward LGBTQI+ people; instead, they feared being seen as insufficiently aggressive on the issue. This calculus drove them to escalate rhetoric. For example, when the NDC’s Francis Sosu was accused of being lukewarm on the anti-gay law, he responded by doubling down and chanting slurs (as detailed earlier) – a microcosm of how the entire party system behaved.

The broad consensus on rejecting LGBTQI+ rights also meant that typical checks and balances – civil society criticism, media scrutiny – had limited political impact. Many media outlets themselves framed the election as partly about “defending cultural values,” often uncritically echoing politicians’ talking points. Some commentators lamented that tribal and religious politics, once frowned upon, had been replaced by sexual minority politics as the new polarising force. The space for any nuanced discussion (such as the human rights implications of the anti-LGBTQ bill) was virtually nonexistent in the mainstream campaign narrative.

Whilst the official party manifestos for 2024 were not overtly focused on LGBTQI+ issues, the weaponisation of those issues was rampant through other campaign vehicles. The parties turned LGBTQI+ identities and rights into political ammunition – a means to question opponents’ moral credibility and to present themselves as guardians of society. This strategy deeply undermined the integrity of the electoral process, reducing a vulnerable minority to a caricatured threat invoked for votes. It also set a policy course where any future leader might feel mandated by election promises to enact repressive anti-LGBTQ+ measures (as Mahama now may). The challenge moving forward will be how to disentangle governance from this manufactured “culture war” and re-center politics on inclusive and factual dialogue.

LGBTQ+ as an Instrument of Political Electioneering: Insights from Former Special Prosecutor Martin Amidu

Martin A. B. K. Amidu, Ghana’s first Special Prosecutor (appointed 2018) and a former Attorney-General and Minister for Justice (2010–2012), offered one of the clearest constitutional critiques of how LGBTQ+ became an electoral wedge in 2024, setting his arguments down on 6 March 2024 and again on 25 March 2024. Drawing on legal history and lived practice inside Ghana’s institutions, he contends that both major parties instrumentalised queer lives for votes, albeit with different tactics: the NDC drove a hardline legislative push and moral panic to energise its base ahead of 7 December 2024, while the NPP largely preferred the “status quo” of Section 104 of the Criminal Offences Act, 1960 (Act 29) to avoid the geopolitical and economic risks of a sweeping new criminal regime. In Amidu’s reading, this wasn’t a spontaneous culture war but the latest turn in a long cycle of partisan conflict where sexual orientation is deployed as a ready-made identity fault line whenever power is up for grabs.

Amidu roots his case in chronology. Parliament’s voice-vote passage of the private member’s bill, the Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill, on 28 February 2024, he argues, was propelled less by reasoned deliberation than by bipartisan fear of appearing “soft,” which suppressed dissent and invited performative homophobia. He anticipated, on 6 March 2024, that President Nana Akufo-Addo would not assent, calling assent “political suicide” given the image he had cultivated as a Western-leaning democrat and the administration’s reliance on external partnerships and financing. Within days, pressure from powerful faith actors intensified: on 5 March 2024, the Catholic Bishops Conference publicly warned of electoral consequences if the President refused to sign, even as the Finance Ministry flagged multi-billion-dollar risks to World Bank flows. For Amidu, these cross-winds revealed a combustible triangle of electoral calculus, faith-based mobilisation, and donor geopolitics that was never going to yield careful lawmaking.

He is equally pointed about process. As suits multiplied, Amanda Odoi’s constitutional challenge initiated in June–July 2023 and renewed with an injunction application on 8 March 2024; Richard Sky’s filing on 5 March 2024, Amidu argued that the separation of powers required restraint from both the Presidency and Parliament while the Supreme Court was seized of the matter. Instead, the confrontation escalated. He castigates the Speaker’s ruling of 20 March 2024 and the surrounding brinkmanship as partisan overreach that strained parliamentary neutrality, compounded constitutional tensions, and substituted institutional dialogue with procedural hardball. In Amidu’s frame, only the Court can legitimately resolve whether, and how, a private member’s bill of this scope passes constitutional muster while interim applications are pending; political actors usurping that role corrodes the guardrails of the 1992 Constitution.

A hallmark of Amidu’s intervention is his historical demystification. He reminds readers that Ghana’s anti-sodomy provision is not an immemorial indigenous norm but a colonial legal transplant: the criminalisation of “unnatural carnal knowledge” was introduced to the Gold Coast in 1892 as an outgrowth of Britain’s Offences Against the Person Act 1861 and then inherited at independence. The claim that today’s criminal framework organically expresses “Ghanaian culture,” he argues, collapses under the weight of its colonial provenance. This matters practically: if the law’s roots are external, deploying “tradition” to justify new punitive layers is a political choice, not destiny. It also matters normatively: a democracy cannot allow contested identities to be turned into permanent emergency legislation through electoral pressure without testing those measures against constitutional rights and the rule of law.

Amidu’s March essays also map the parties’ divergent – but converging -political logics. He portrays the NDC’s strategy as a deliberate elevation of anti-LGBTQI+ rhetoric into a moral litmus test to win 2024, aided by a Speaker who, in his view, abandoned institutional impartiality. He reads the NPP’s strategy as an effort to avoid international censure and macroeconomic blowback by keeping to Act 29 while signaling cultural conservatism to its base, a balancing act he believed would culminate in presidential non-assent. In parallel, he notes how faith mobilisation (early March) and donor concerns (throughout March) hardened positions on both sides, leaving little room for principled compromise or due-process pacing.

From an advocacy and human-rights vantage point, Amidu’s warning is stark and useful. Elevating LGBTQ+ lives into a campaign tool doesn’t just endanger queer Ghanaians; it destabilise institutional roles, invites constitutional shortcuts, and turns the Supreme Court into a battlefield for partisan theatrics rather than a forum for principled adjudication. His proposed way back, allow the Court to decide now, and again if the law ever comes into force; and if politicians insist that “the people” demand punitive policy, test that claim through a law-governed referendum, seeks to remove existential questions about minority rights from the churn of electioneering and to re-center constitutional method. It is also a reminder to the incoming and future governments that durable policy rests not on fear, but on legality, rights, and institutional respect.

Finally, Amidu’s timeline foreshadowed the political outcome and its aftermath. 2024 would indeed be fought with LGBTQ+ as a wedge; legal challenges would persist; faith and donor pressure would pull in opposite directions; and the President would decline to assent despite intense agitation, all of which shaped the climate in which John Dramani Mahama won the December 2024 election, the NDC secured a two-thirds majority in Parliament, and Ghana entered 2025 with a lapsed bill and a frayed discourse. For a report committed to inclusive democracy, Amidu’s core insight is invaluable: de-politicise queer existence, restore constitutional process, and pursue reform through facts and rights rather than through the expediencies of fear.

Public Opinion, Electoral Impact, and the Fate of the Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Bill

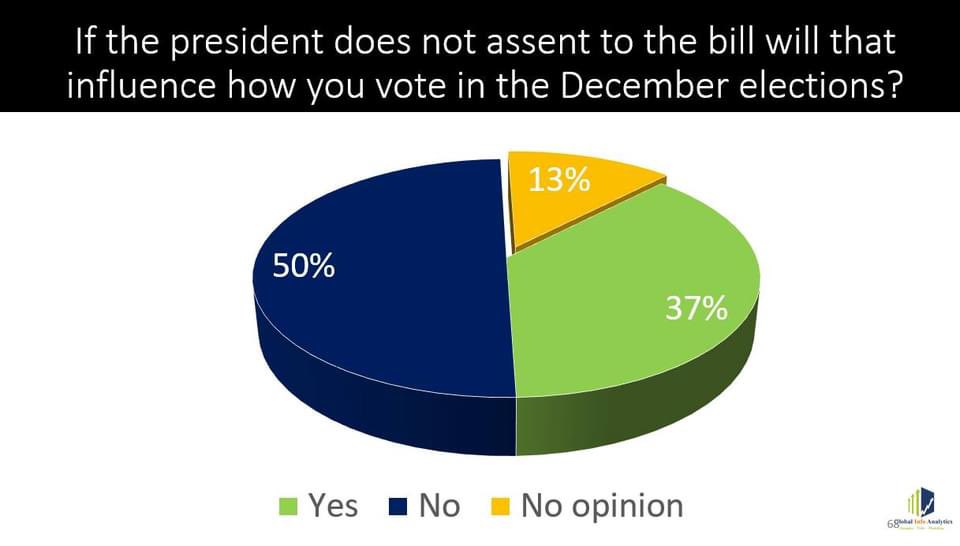

A 2024 pre-election poll by Global Info Analytics revealed the deep political salience of the anti-LGBTQ+ debate. According to the survey, over 37% of voters said that if President Nana Akufo-Addo did not assent to the Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Bill, it would influence how they voted in the December 2024 general elections. This underscores how the bill, framed by politicians as a litmus test of “values” and national sovereignty, became a deciding electoral issue rather than a technical legislative matter. At the same time, half of respondents indicated it would not affect their vote, reflecting a divided electorate and suggesting that while homophobia was a powerful campaign tool, it was not the only driver of voter choice.

Global Info Analytics Data: 2024 pre-election poll

The bill itself was passed by Parliament with bipartisan support on 28 February 2024, but following constitutional challenges lodged at the Supreme Court, President Akufo-Addo refused to assent to it before leaving office. As a result, the bill lapsed and expired with the end of that parliamentary session. This decision became a major talking point during the campaign, feeding narratives of betrayal among hardline advocates and mobilizing anger among conservative voters.

In the aftermath of the elections, won by John Dramani Mahama and the NDC with a two-thirds parliamentary majority, Moses Foh-Amoaning, Executive Secretary of the National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values, claimed the NPP’s defeat was directly linked to the bill. Speaking on GTV’s Breakfast Show, he argued that the President’s refusal to sign the legislation represented a “sad commentary on his legacy” and alienated a critical mass of voters. In his words, “God rejected the NPP for not signing the anti-LGBTQ Bill.”

Foh-Amoaning expressed confidence that newly sworn-in President Mahama would not resist popular will by refusing to assent to a similar bill in the future:

“I don’t think President Mahama will refuse to sign the bill, as that would go against the will of Ghanaians.”

He further suggested that once the law is enacted, Ghana would be in a stronger position to attract resources to tackle national challenges【source: GhanaWeb】.

The polling data, combined with the legislative timeline and post-election commentary, reveals that the anti-LGBTQ+ bill served both as a wedge issue and as an electoral weapon. Its journey from parliamentary passage to presidential rejection and eventual expiration illustrates the tensions between constitutional governance, international obligations, and populist demands. Importantly, while the NPP suffered significant losses, it is too reductive to claim the bill was the sole cause; nevertheless, it clearly shaped the electoral climate and was leveraged heavily by political actors and advocacy groups.

Impact on LGBTQI+ Communities in 2024

The toxic climate of the 2024 elections had real and devastating consequences for LGBTQI+ individuals in Ghana. Even though the anti-LGBTQI+ bill did not become law in 2024, the mere fact of its parliamentary passage – combined with the incendiary campaign rhetoric – unleashed a wave of discrimination, abuse, and fear. Human rights organisations documented a sharp uptick in incidents targeting people known or suspected to be LGBTQI+ during the election year. According to local LGBTQI+ rights groups, 2024 saw the highest number of human rights violations against LGBTQI+ persons in recent memory, including forced evictions from homes, physical assaults, blackmail and extortion, online doxxing and threats, and arbitrary arrests. The election season essentially provided social sanction for homophobes to act on their prejudices, knowing that politicians themselves were echoing anti-gay sentiments.

One immediate impact was on housing security. Reports surfaced of landlords and families expelling tenants or relatives merely over rumors of their sexual orientation, citing the “new law” as justification – even though the bill was not actually signed, its passage emboldened such acts. Amnesty International noted that since the bill’s introduction, LGBTQI+ people had already been reporting “forced evictions [and] loss of jobs” due to increased stigma. This trend intensified around the campaign period as anti-LGBTQ talk grew louder. In multiple cases, individuals were rendered homeless overnight after being outed in their community; some were evicted by landlords who feared harboring an LGBTQ person might soon be a crime. Others lost employment when employers leveraged the hostile climate to fire them under false pretenses. The socio-economic toll on LGBTQI+ Ghanaians – many of whom were already marginalised – was severe.

Physical violence against LGBTQI+ persons also spiked. The atmosphere of hate rallies and “othering” propaganda contributed to an uptick in assaults and lynching attempts. Community leaders who might normally calm such situations were less inclined to intervene, given that national leaders were vilifying LGBTQI+ people on stage. The culture of impunity grew – perpetrators of anti-LGBTQ violence often felt they had societal approval. Indeed, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that the rhetoric and pending law were creating a “license for violence” in Ghana, as people felt “emboldened to adopt oppressive measures with impunity.” Queer individuals increasingly went into hiding or avoided public spaces for fear of being recognised and attacked. Community support organisations recorded cases of LGBTQI+ persons being harassed or beaten by vigilantes who cited “cleansing our community” as motive.

Another area of impact was mental health and self-censorship. The relentless demonisation during the campaign had a chilling effect: many LGBTQI+ people experienced heightened anxiety, depression, and a sense of betrayal by their nation. Psychological support service providers noted that queer youth, in particular, expressed hopelessness, with some contemplating suicide as they felt their country hated them. Social media, which can be a lifeline for LGBTQ+ youth seeking community, was flooded with hateful content throughout 2024, making even online spaces feel unsafe. Activists reported an increase in calls to helplines and requests for relocation or asylum assistance. Rainbow Railroad, an international NGO assisting LGBTQI+ refugees, noted a surge of Ghanaians seeking help and anticipated even more if the situation worsened.

Crucially, the climate also undermined access to healthcare and social services for LGBTQI+ individuals. Even prior to 2024, Ghana’s LGBTQI+ community faced stigma in healthcare settings, especially for services related to HIV and AIDS. The campaign’s hostile rhetoric greatly exacerbated this. A study in The Lancet has shown that such criminalising environments correlate with higher HIV infection rates among men who have sex with men – a concern now very relevant to Ghana. Health workers themselves felt intimidated; some worried that providing care to a transgender or gay client could later be used to accuse them of “promoting” LGBTQ activities under the new law. The International AIDS Society warned that the bill and surrounding homophobia would “set back the substantial gains made towards ending the HIV epidemic”, as it would drive vulnerable groups away from testing and treatment. Indeed, as the IAS President Sharon Lewin put it, “criminalizing any population fuels the HIV pandemic by excluding people from testing, treatment and care.” 2024 offered a live demonstration of this principle: stigma hindered healthcare access. For example, the NPP’s campaign ad mischaracterizing Mahama’s call to reduce stigma for MSM healthcare likely scared some LGBTQI+ persons from seeking care, since even a former President’s mild pro-health comment was twisted into something nefarious. In short, the politicisation of LGBTQI+ identity directly harmed public health efforts and individual well-being.

Finally, it must be noted that the legal uncertainty during 2024 – with the bill passed but not signed – created chaos for rule of law. These actions sowed fear and disrupted community life. The Ghana Police Service largely failed to protect LGBTQI+ citizens; there were no known prosecutions of those who attacked LGBTQI+ persons, whereas LGBTQI+ victims often could not even safely report crimes against them.

In summary, the 2024 elections’ anti-LGBTQI+ fervor had far-reaching negative impacts on the community: from loss of homes and livelihoods, to increased violence and trauma, to reduced access to vital services. Ghana’s LGBTQI+ population – already criminalised under an old colonial law – found themselves even more marginalised. Many described 2024 as one of the most difficult years in memory for queer Ghanaians, a time when they felt scapegoated and abandoned by leaders sworn to protect all citizens. The damage done will not be easily erased; mistrust between the LGBTQI+ community and state institutions deepened, and the community’s sense of belonging in their own country was deeply shaken. Any path forward must reckon with healing these wounds and ensuring that political rhetoric never again incites such human rights violations.

International Influence on Domestic Anti-LGBTQI+ Narratives (2024)

Throughout 2024, Ghana’s domestic anti-LGBTQI+ narratives were both shaped by and reactive to international influences. The debate around the anti-LGBTQI+ bill and the election did not occur in a vacuum – global actors and events played significant roles, which Ghanaian politicians either harnessed to support their stance or cast as antagonistic interference.

On one hand, international conservative networks and actors actively bolstered Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ movement. The National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values (led by lawyer Moses Foh-Amoaning) cultivated alliances with American evangelical and right-wing organisations which provided ideological and tactical support. Groups like Family Watch International and the World Congress of Families (WCF) – known for exporting anti-LGBT agendas to Africa – were in communication with Ghanaian proponents of the bill. Foh-Amoaning openly acknowledged in 2023 that his coalition was collaborating with U.S.-based conservative outfits, and even planning to introduce their anti-LGBTQ “education” programs into Ghanaian schools. By 2024, these links were bearing fruit: resources (from literature to strategy guidance) flowed from Western anti-rights lobbyists into Ghana. This global networking helped frame Ghana’s issue as part of a larger “culture war” defending family values worldwide. It’s notable that Sam George and other bill sponsors were featured at international events organized by ultra-conservative networks. In 2023, Sam George spoke at the Political Network for Values summit at the UN in New York – rubbing shoulders with far-right activists from multiple continents. Such exposure strengthened his resolve and credibility among local constituents who saw him engaging on a world stage to “fight LGBTQ”. In 2024, these ties continued to give the NDC’s anti-LGBTQ crusaders a sense of moral legitimacy beyond Ghana’s borders. The influence also went both ways: Ghana’s actions were celebrated by anti-LGBT forces abroad, reinforcing domestic actors. For example, international anti-LGBT campaigners held up Ghana (alongside Uganda and Kenya) as a model, creating a feedback loop that emboldened Ghanaian politicians to push further. The regional contagion effect was real – Uganda’s passage of a harsh Anti-Homosexuality Act in May 2023 (with vociferous support from U.S. evangelicals) set a precedent, and Ghanaian advocates explicitly cited Uganda as inspiration to not yield to Western criticism. By 2024, Ghana’s bill was seen as part of a wave of similar bills across Africa, a point of pride among its supporters. In short, international right-wing influence provided both strategic backing and comparative justification (“we are part of a righteous trend”) for Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ narrative.

On the other hand, international human rights pressure and geopolitical considerations heavily influenced the discourse – often becoming a foil for local politicians. Western governments, international NGOs, and the United Nations spoke out strongly against Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ bill in 2024. The bill’s passage in Parliament was met with “international criticism” and warnings from diplomats and UN experts that it violated fundamental rights. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and global human rights organizations (like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch) urged President Akufo-Addo to veto the bill, highlighting the dangers it posed. For example, Amnesty International’s Ghana director blasted the bill as “shocking and deeply disappointing… one of the most draconian in Africa” and explicitly called on Akufo-Addo not to sign it. Similarly, the World Bank and other multilateral partners indirectly weighed in: as noted, a leaked memo from Ghana’s own financial authorities warned of losing US$3.8 billion in funding if the bill became law, implying that international donors were alarmed. This external pressure became grist for domestic political rhetoric. NDC politicians seized on it to argue the NPP lacked the courage to uphold Ghana’s values – claiming the government was cowed by threats of aid cuts. The notion of “sovereignty vs. aid” became a talking point. Mahama and others essentially said: We won’t trade our culture for dollars; the NPP will. In doing so, they tapped into a nationalist sentiment and reframed international human rights advocacy as neo-colonial bullying. The NPP, in a defensive posture, insisted they still supported the bill but were delayed by constitutional procedure (the court cases) – yet the perception stuck that Akufo-Addo heeded Western warnings over the will of Ghanaians. Thus, international criticism inadvertently provided ammunition to hardliners who cast themselves as patriots resisting foreign diktat.

However, international influence was not uniformly negative. There was also support for LGBTQI+ Ghanaians from the diaspora and allies abroad during 2024. Global media coverage of the bill and election put a spotlight on Ghana’s LGBTQI+ plight, leading to solidarity actions. For instance, protests were held by African LGBTQ activists in front of Ghanaian embassies in cities like Pretoria and London. The U.S. Vice-President’s visit in early 2023 (Kamala Harris) and statements by European leaders had earlier signaled international concern for LGBTQI+ rights in Africa, which lingered into 2024 discussions. Ghana’s government officials bristled at such lectures, but they did factor into the narrative: NPP spokespeople occasionally argued that passing the law carelessly could jeopardize Ghana’s relations and economic programs (implicitly validating some foreign concerns). Indeed, the IMF bailout context made the threat of sanctions or withheld funds more tangible. This pragmatic argument for caution, while not loudly advertised, perhaps influenced Akufo-Addo’s last-minute decision not to sign the bill.

Furthermore, Ghana’s situation in 2024 was frequently compared to other countries in international forums. Some African nations – e.g. Namibia’s parliament banning same-sex marriage or Kenya debating its own anti-LGBTQ bill – were cited by Ghanaian conservatives as evidence of a continental movement. Conversely, Ghana was under scrutiny in bodies like the UN Human Rights Council (ironic, since Ghana was elected to the Council even as it passed this bill). The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights had in late 2023 issued a strong statement against laws criminalising sexual orientation, which Ghana’s parliament ignored. Still, these international normative pressures lay the groundwork for potential legal challenges in the future, and they gave hope to local activists that not all external voices were against them.

In summary, 2024 demonstrated that Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ narratives were deeply entangled with global interactions. International anti-LGBTQ campaigners provided encouragement and a playbook to Ghanaian actors, reinforcing the local movement. At the same time, international human rights advocates and development partners applied pressure in the opposite direction, which Ghanaian politicians then spun to their advantage domestically by invoking sovereignty. This push-and-pull affected the trajectory of the anti-LGBTQI+ bill (stalling its assent) and was cynically exploited in campaign messaging. It also positioned Ghana as a key battleground in a larger international conflict over LGBTQI+ rights. The challenge ahead will be navigating these international currents in a way that supports Ghana’s democratic and human rights commitments. As of 2025, President Mahama faces a decision that encapsulates this tension: appease a domestic base expecting the anti-LGBTQI+ law, or heed international and constitutional principles warning against it. The international community’s role, therefore, remains crucial – both in discouraging state-sponsored homophobia and in supporting those within Ghana advocating for tolerance and equality.

Recommendations

In light of the findings above, it is imperative that various stakeholders take concrete actions to counter hate speech, misinformation, and human rights abuses targeting LGBTQI+ persons. The following multi-faceted recommendations are offered, tailored to specific actors. The overarching goal is to promote an inclusive democracy in Ghana where no group is demonised for political gain and where fundamental rights are upheld regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. These steps seek to address both immediate harms and long-term cultural and institutional change.

Government of Ghana (Executive Branch)

- Publicly Uphold Constitutional Values: The President and government ministers should affirm that all Ghanaians, including LGBTQI+ persons, are entitled to the constitutional guarantees of dignity, freedom, and equality. A clear presidential statement condemning violence and hate speech against any group – without ambiguity – would set the tone that the state does not sanction bigotry.

- Veto or Amend Anti-LGBTQI+ Legislation: The President should refuse to assent to any revival of the “Human Sexual Rights and Family Values” Bill in its current draconian form. If legislation is considered, it must be significantly amended to remove provisions that criminalise identity or expression and that violate human rights. Ideally, the executive should work with Parliament to pause and reassess the need for such a law in light of constitutional and international human rights obligations.

- Promote Dialogue and Tolerance: The government can initiate or support a national dialogue on social cohesion and inclusion. This could involve town-hall meetings or forums (including religious and traditional leaders, youth, etc.) to foster understanding rather than fear of differences. Government-endorsed public education campaigns highlighting Ghana’s tradition of peace and neighborly love (and how that extends to all) could counter the hateful narratives.

- Avoid Politicising Minority Rights: Going forward, the executive should refrain from using LGBTQI+ issues (or any minority rights) as a tool for political mobilisation. Cabinet members and spokespeople must stick to issue-based campaigning and governance. The President should set an example by focusing discourse on policy solutions (economy, health, education) and by swiftly disavowing any appointee who makes derogatory statements about minority groups.

- Strengthen Protections and Services: Direct relevant ministries to strengthen protections for vulnerable groups. For instance, the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, and the Ministry of Interior should develop protocols for protecting persons who face discrimination or violence due to sexual orientation/gender. Ensure that social protection programs and emergency shelters are accessible to those displaced by homophobic abuse. The health ministry should quietly continue (and even expand) key population health services, ensuring that anti-LGBTQI+ sentiment does not derail HIV/AIDS and mental health programs. International assistance can be sought to fund these initiatives discreetly.

Parliament and Political Parties

- Depoliticise LGBTQI+ Identities: Political parties must commit to exorcising LGBTQI+ issues from partisan point-scoring. Both the majority and opposition in Parliament should agree (perhaps via a bipartisan resolution or code of conduct) that they will not use hate speech or disinformation as political tools. They should publicly acknowledge that exploiting social divisions undermines national unity and democracy.

- Review and Reform Legislation: Parliament, with its new composition, should critically review any pending or future bills affecting human rights. Legislators ought to seek expert input (from Ghana’s Human Rights Commission, constitutional lawyers, public health experts, etc.) on the implications of laws like the anti-LGBTQI+ bill. Sections that infringe on free speech, privacy, and other rights should be removed or reworked. Better yet, Parliament could table comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation that protects all citizens – including on grounds of sex, religion, and sexual orientation – to show a commitment to equality (even if passage of such a law may be challenging now, starting the conversation is important).

- Enforce Ethical Campaigning: The leadership of both NDC and NPP (and other parties) should enforce internal rules against campaigning with hateful or false content. Party communicators and surrogates who propagate clear hate speech or fraudulent claims should face disciplinary measures (e.g., removal from campaign team or public apology). In future manifestos, parties should focus on policy and refrain from inflammatory “moral” pledges that target any community for repression.

- Constitutional Awareness: Parliamentarians should remember Ghana’s international commitments (such as treaties on civil and political rights) and the supreme law of the land. When considering laws like the anti-LGBTQI+ bill, MPs must balance popular sentiment with constitutional principles. An orientation or workshop for MPs on human rights and constitutional limits (possibly facilitated by the Judiciary or civil society experts) could be beneficial, so lawmakers craft laws that can withstand judicial scrutiny and respect minority rights.